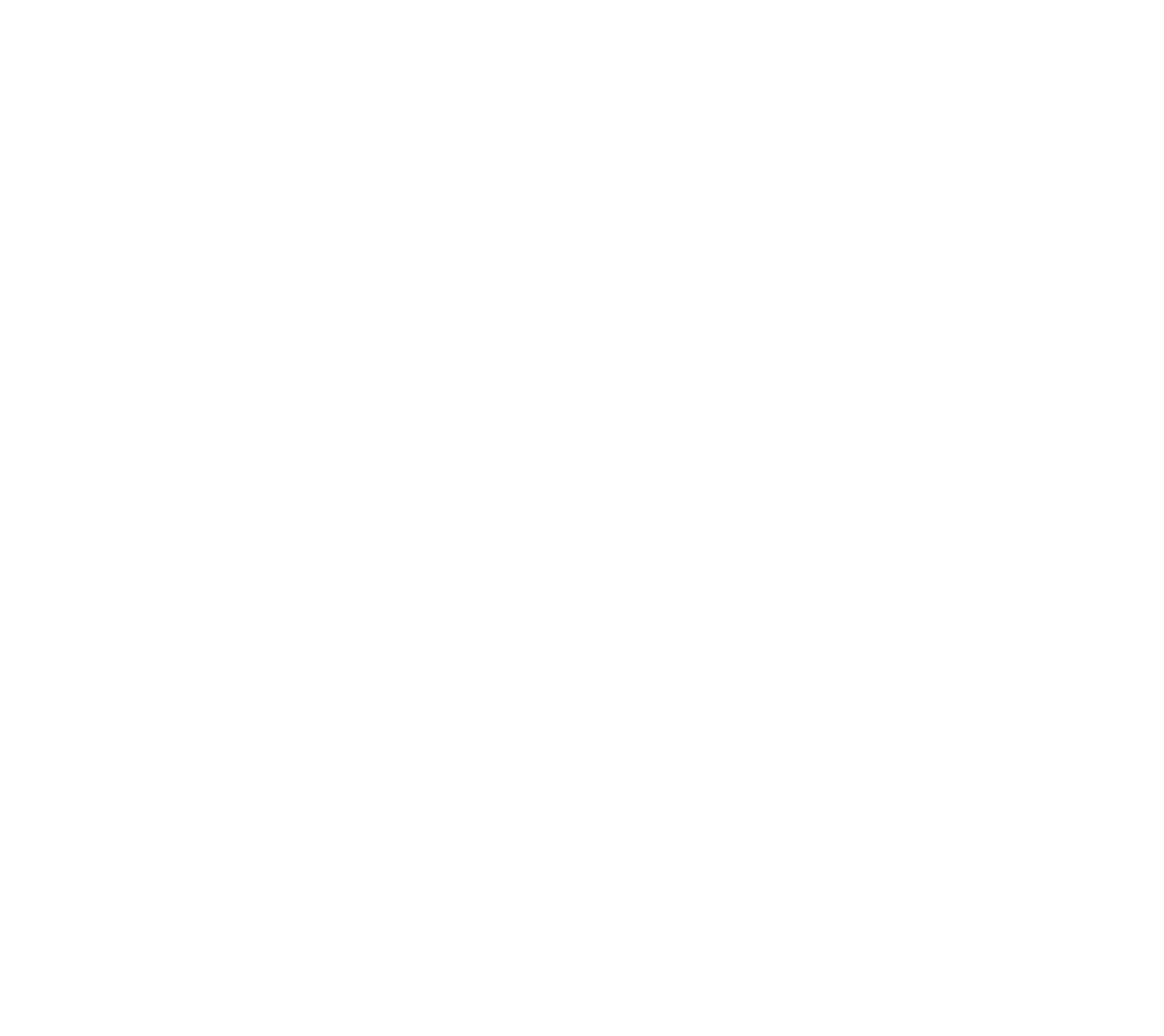

Atherton Cotton Mills has not always housed shops, stores, restaurants, and bars. It is one of many examples of adaptive reuse in Charlotte, in which an existing structure is used for a new purpose. Located along South Boulevard, Atherton was the first textile mill in Charlotte’s newly planned community of Dilworth and a significant catalyst for its growth.

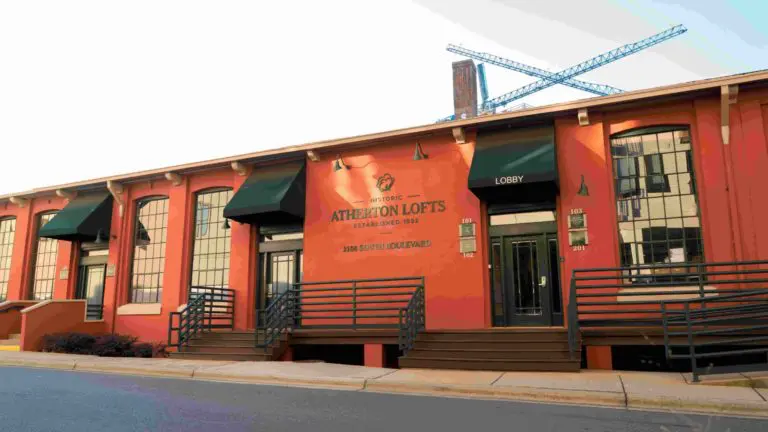

Daniel Augustus (D.A.) Tompkins, R.M. Miller, Jr., and E.A. Smith, all associates in the D.A. Tompkins Company, filed the incorporation papers for Atherton Cotton Mills on July 18, 1892. It was Charlotte’s sixth largest cotton mill and steam power at the time, drawing its power from the Summit Hill Gold mine. Atherton Cotton Mills created jobs and helped propel the Charlotte area into an industrial powerhouse.

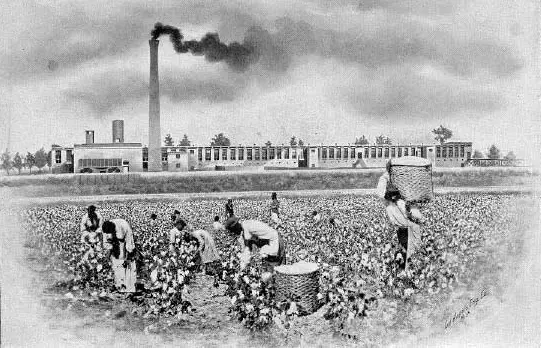

Atherton Cotton Mills was a part of the larger textile industry movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century throughout Charlotte and North Carolina. The success of that movement was aided by “New South” entrepreneurs like D.A. Tompkins who embraced the Industrial Revolution. They realized that, in order to prosper after the emancipation of the enslaved and the Civil War, the South should not only grow raw materials like cotton and tobacco but needed to process those raw materials.

By 1893, Atherton Cotton Mills was open for business, manufacturing 5,000 spindles of yarn goods. Atherton was constructed with growth in mind, so there was ample floor space for more production. By 1896, there was enough machinery for 10,000 spindles and Atherton employed 300 men, women, and children who lived in its mill village. The mill village had the Atherton Lyceum, a two-story multi-purpose building that housed a school, general store, Sunday School classroom, and town hall. The village also included 50 one-story homes. Creating mill villages to house employees was common practice during that time. These mill villages were typically company-owned, and Atherton Cotton Mills was no different.

Nearly 95 percent of Southern textile families lived in mill villages at the turn of the century. Mill villages were created to control, as mill owners and supervisors tightly controlled daily life within the villages. Mills offered steady wages, and the company store and mill houses were strong attractions for those looking for work. Mill owners used paternalism, or the practice of restricting their workers’ freedoms, for the supposed best interest of the workers. Paternalism took hold because of the sheer number of people coming to work, all needing services and housing. Mill owners were the only people with the necessary funds to provide those things.

The mill owner provided things like shelter, jobs, schooling, medical care, and authority in the personal lives of their employees. Mill workers did almost all of their shopping at the company store, where they were usually charged more for goods than stores outside the mill village. Some mills gave out coupon books to their employees so they could shop in the company store. Mills provided schooling for children but often attended sporadically or for a few years because child labor was necessary for many families’ income. Churches were common in mill villages where pastors preached company-approved sermons.

Mill life at Atherton excluded Black workers. Tompkins believed that Black people were useful laborers but believed they should remain farm and field laborers and be left out of textile work. That was a common belief and practice of southern textile owners at the time. The 1890s when Atherton Cotton Mills was founded, was an important turning point for the nation. Segregation and disenfranchisement of Blacks became the norm in all aspects of society. Tompkins was a white supremacist Democrat who believed that segregation upheld white supremacy and was necessary for the growth of capitalism, particularly in the New South. Tompkins owned the Charlotte Daily Observer, where he would promote his own causes and beliefs about industrialism.

The Atherton Mill and village served as the necessary catalyst for Dilworth’s residential and industrial growth. Dilworth saw little growth at first, and it nearly failed. The initial Dilworth plan included residential streets, a park, and a factory district. Dilworth was Charlotte’s very first streetcar suburb. The announcement that Atherton Cotton Mills was coming to the neighborhood kicked off the growth of the factory district. Once Atherton opened, other mills followed, drawing in more people. Dilworth began to prosper.

Atherton Cotton Mills was purchased by a group of Gaston County plant operators in 1922 and reorganized as Atherton Mill, Inc. In the 1920s, Dilworth was starting to lose factories. By the Great Depression, several mills shut down or relocated. In 1933, the mill was foreclosed, and Atherton Mills, Inc. lost ownership. It sat vacant until 1937, when it was purchased by J. Schoenith Company, a candy, baked good, and peanut manufacturer, which operated until the late 1960s. Schoenith built a warehouse and office building. Until its repurposing, it was used by various wholesaling and textile-based companies. In the 1990s, Atherton Mills began to take on the shape we are most familiar with today. Thanks to adaptive reuse, Atherton Cotton Mills is now a residential community and shopping center home to national retailers like Luluemon, restaurants like Cava, community space, and public art.