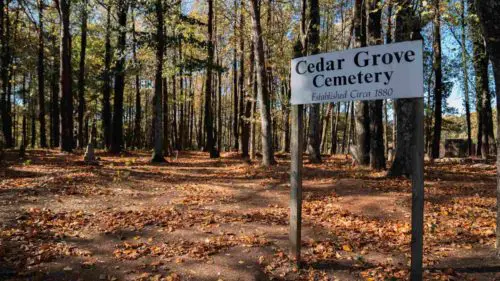

Cedar Grove Cemetery at 2375 Hildebrand Street was once more than 67 acres of land designated as a planned cemetery for African Americans. Over the years, the land was apportioned to developers and the City of Charlotte, leaving just 1.8 acres of the original cemetery with an unknown number of graves. Why did African Americans need their own cemeteries and burial grounds?

Black cemeteries and burial grounds were needed in the Jim Crow era. Because of legal segregation and the social inequalities it supported, it was necessary for Black people to create their own institutions and businesses like newspapers, stores, houses of worship, and, in this case, cemeteries. Even in death, segregation separated white and Black Charlotteans.

In Charlotte, there were two cemeteries, Elmwood and Pinewood. Both were established in 1853 beside one another, but separated by race and a fence. Elmwood Cemetery was a whites-only cemetery, and Pinewood Cemetery was for Charlotte’s Black residents. Those two cemeteries remained separated until 1969, when Charlotte’s first Black city council member Fred Alexander lead the fight to bring the fence down. In January of 1969, Alexander watched the fence be torn down. Alexander share with Charlotte News: “…it didn’t mean anything to white folks, but when I was a little boy, I used to come here and see this and to me it was just the worst thing in the world.”

The funeral industry first came to Charlotte in 1887, with the first white mortician arriving in the area, which meant that Charlotte’s Black community would need its own mortician. The rise of the Black funerary industry in Charlotte created more Black wealth, resulting in the diversification of the businesses, making products like life insurance and burial services, ultimately leading to the creation of companies to manage those businesses.

The Cedar Grove Cemetery Association (CGCA) is an example of one of those businesses founded on August 21, 1915. The CGCA sold plots and graves in Cedar Grove Cemetery and maintained the Cemetery. The organization’s officers were white and Black community members: Robert B. Bruce was a bishop in the A.M.E. Zion Church, J.T. Sanders was a lawyer and financier, and Dr. Allen Atkins Wyche was a physician. The CGCA’s white officers included John Misenheimer, the owner of Oaklawn Cemetery, and W.M. Tye, a tax assessor.

The CGCA purchased 67 acres to start a cemetery and conducted burials on the site from 1915 to 1925. This was a burial ground before the establishment of the CGCA. In 1925, the CGCA sold the land to T.T. and Sallie Cole to settle its land debts, owning more than $15,000 in mortgage costs on the land. In February of 1925, the CGCA purchased 17 acres back, only a portion of its original size. By 1955, the CGCA had dissolved as all its founding members had passed away, and the company was inactive.

John Shead Davidson of Davidson Brothers Funeral Home in Charlotte attempted to purchase the 17-acre Cemetery but could not because there was a claimant to the property. On October 29, 1956, the 17-acre Cemetery was auctioned off to the Board of School Commissioners of the City of Charlotte (precursor to Charlotte-Mecklenburg School).

The City built University Park Elementary School on the 17-acre parcel of land, which included a 1.8-acre tract of land that the CGCA had used for burials. In 1957, Davidson purchased the 1.8-acre tract, began using it as a burial ground, and sold burial plots again under the name Cedar “Hill” Cemetery. The Cemetery is the final resting place of several prominent members of Charlotte’s Black community, like Bishop Robert Bruce, and a number of Black veterans.

Davidson and his brothers became the operators of Cedar Grove Cemetery, responsible for its upkeep. When Davidson died in 1972 at 100 years old, care for the Cemetery stopped since he had outlived his brothers and other business partners. The deed for the Cemetery passed to Davidson’s two daughters, both of whom did not have children. So when Davidson’s daughter passed, Cedar Grove Cemetery was legally abandoned. It fell into disrepair, becoming overgrown with vegetation.

The state, county, and city do not maintain the property because the property has no living owner or caretaker and is privately held and untaxed. Cedar Grove Cemetery’s upkeep and clean up has fallen to volunteers and organizations like Save Cedar Grove. Save Cedar Grove has worked to clear the underbrush from the cemetery and map out the landscape, which makes accessing graves easier. People still visit their loved ones placing gifts, flags, and flowers upon the graves. It is unknown how many graves remain in the cemetery, as some grave markers still stand but some have been destroyed or lost.

Save Cedar Grove is an organization working toward restoring the space and making it a “place of peace and pride for the community and those who rest within it.” When asked what the cemetery means to the community Che´ Abdullah, a representative of the Save Cedar Grove organization, said that “the people that are buried there are the people that made that place and much of Charlotte, that’s what it means to the community. Abdullah also discussed the importance of saving and celebrating the cemetery, saying: “It’s an opportunity to celebrate the builders of Brooklyn, Beatties Ford, and the City of Charlotte and the country through the military service.”