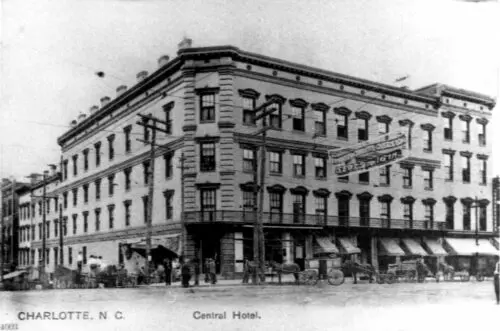

Have you ever noticed the old red brick house on North Brevard Street in Uptown? It is known as the Treloar House, and it seems out of place and out of time among the modern high rises and skyscrapers. But the home has an interesting history and offers the last vestige of the Old First Ward neighborhood.

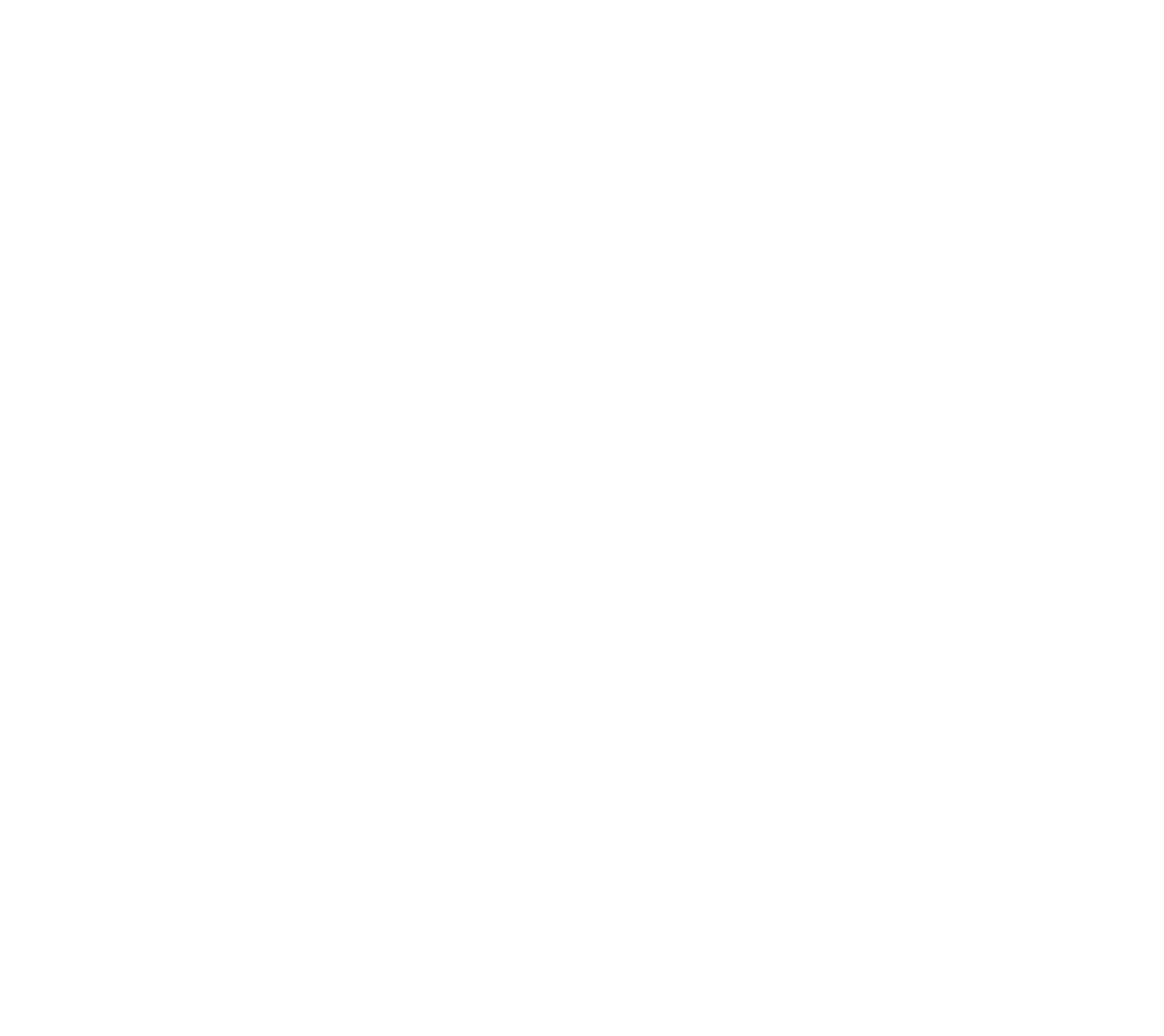

William Treloar, for whom the house is named, was a man of ambition and adventure. Born in the mining region of Cornwall, England, he set his sights on North Carolina, the site of the first gold rush in the United States. In 1884 at age 19, he emigrated to the United States, driven by the allure of gold. His entrepreneurial spirit led him to acquire interest in various gold mines, including Gold Hill, Rowan County, Pioneer Mills in Cabarrus, and the Ray Mine in Mecklenburg County. He also established a successful general merchandising business in Salisbury, North Carolina.

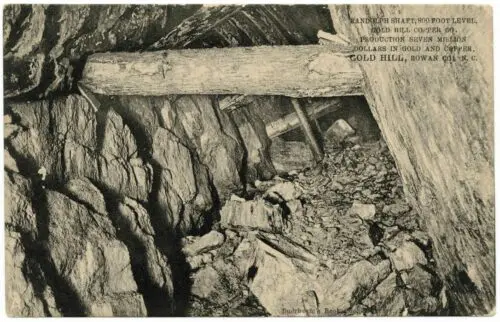

When he moved to Charlotte in the 1850s, he bought the Central Hotel, one of Charlotte’s largest. He also owned a row of store buildings called Granite Row, later called Treloar’s Hall. When the Civil War broke out, he sold Treloar’s Hall and the Central Hotel and moved his family to Philadelphia while the Civil War raged in the South.

Treloar and his family moved back south sixteen years after the war in 1881. They returned to Charlotte in 1886 and began building their double house on the affluent North Brevard Street in Charlotte’s First Ward neighborhood. A double house is a home in which the owner lived on one side and rented the other side out. It is a row house-style home, a style that was popular in Philadelphia.

The First Ward dates to 1869, when the city’s leaders split the city into four election districts: the four wards. First Ward was the home of rich and poor, black and white. It was one of the city’s most racially and economically integrated areas at the time. It contained some of the city’s largest homes, like the Treloar House, and some of its finest businesses. First Ward was an early example of integration in Charlotte, and early city directories showed a mixture of Black and white residents. Most of the residents of First Ward seemed to be working-class white and Black residents, with some upper- and middle-class whites on the streets closest to the Square. First Ward had churches like First United Presbyterian Church, banks like Merchants and Farmers, and businesses like the Carolina Theatre. Urban renewal and demolition of First Ward began in 1967.

On January 4, 1887, the Treloars put an advertisement out describing their home as having eleven rooms and every convenience a tenant would want, and telling the tenants, specifically women, they were invited to live there. The Treloars were to live on the Seventh Street side of the home. The home was partly modeled after their next-door neighbor’s, Samuel P. Smith, a wealthy bank president and elected official. The Smith and Treloar families got along well, as Julia Treloar, daughter of William Treloar, married a Smith son. The couple lived in the Treloar home into their old age. The Treloars, Smiths, and renters lived comfortably in the home for nearly fifty years

The Great Depression caused the Treloars to lose their family home to foreclosure in 1934. For thirteen years, the house was rented to various tenants until it was purchased in 1947 and leased to the Charlotte Auto Parts Company. In the 1980s, the home became Oren Alexander Bail Bonds. The home has sat vacant since the 1980s and its inside is dilapidated. It is currently owned by Levine Properties.

Daniel Levine president of Levine properties has said “he plans to restore the home. He wants to lease the space to a food-service operator. He would like it to have a diner feel, where you can come and get breakfast, lunch or dinner and take in views of the city.”

If you drive by the Treloar House today, you will notice a poem on the brick wall that faces Seventh Street. That poem is a part of the Wall of Poems of Charlotte project, which weaves poetry into everyday life. The project’s creators picked buildings and structures easily visible to workers, residents, and passersby in cars, on public transit, and on foot. All the poems are by North Carolina poets. When choosing a poem for a building, the creators try to take the building’s history, neighbors, and stories. The poem on the Treloar House is called “Bus Stop” by North Carolina poet Donald Justice.