Johnson C. Smith University (JCSU) is Charlotte’s only historically Black college or university (HBCU) and one of twelve in North Carolina. Colleges and universities are often responsible for the continued growth of cities and towns. How has Johnson C. Smith University helped the city of Charlotte grow?

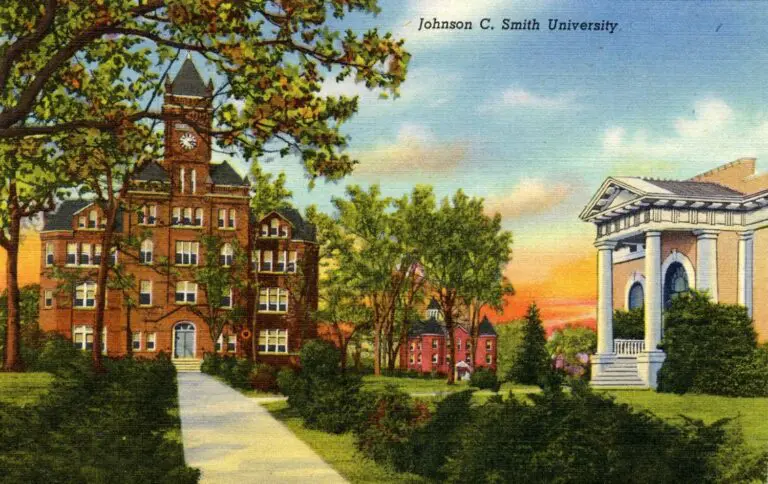

JCSU was established in the aftermath of the Civil War in 1867 as the Freedmen’s College of North Carolina. The school was created by two Presbyterian leaders, Samuel C. Alexander and former enslaver and Confederate soldier Willis L. Miller, in Charlotte to educate preachers and teachers among formerly enslaved people who made up 40% of Mecklenburg County’s population at the time. The first buildings used for the school were wooden structures that were once a part of the Confederate Naval Yard in what we know as Uptown. The wooden structures were moved from Uptown to Northwest Charlotte to an 8-acre plot of land donated by former Confederate Colonel William R. Myers. Alexander and Willis received a donation of $1,400 from Mary Biddle; the school was renamed Henry J. Biddle Memorial Institute in honor of her late husband, Henry.

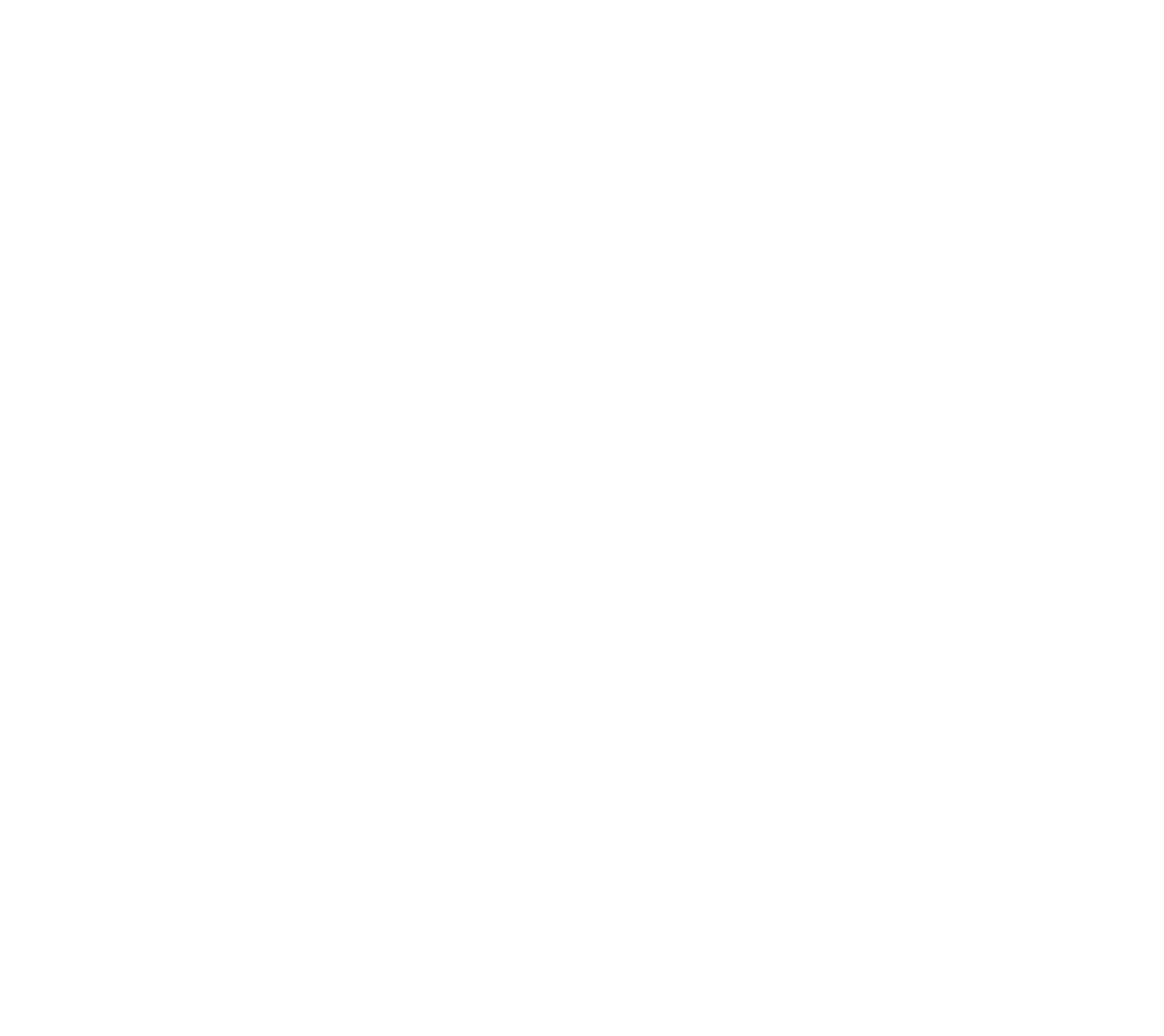

Biddle Memorial Hall was erected in 1884, it was the first substantial building constructed on the current campus. It is the oldest surviving building on campus. Originally it housed an auditorium, the President’s offices, the Business Office, the campus’s first library, classrooms, and restrooms.

JCSU quickly developed a curriculum that fit its nature as a training ground for educators and teachers. In 1912, they formally added a teaching program in English, history, language, music, and science. In 1923, Jane Smith made a significant donation that helped with the construction of several buildings on campus, and the school was renamed in honor of her late husband. Johnson C. Smith. The following year, the university was accredited by the North Carolina Department of Education as a four-year university.

JCSU continued to grow in 1928 when it implemented a two-year pre-med curriculum. JCSU grew again in 1932 when it became a coeducational institution due to an agreement with Barber-Scotia Junior College, a historically black school for women in Concord. Baber-Scotia Junior College sent its graduates to JCSU to complete their degrees. That arrangement continued until 1941, when JCSU began admitting female first-year students.

Early in its history, JCSU was already helping to populate and serve as a catalyst for growth in West Charlotte. When the university elected its first president, Reverend Stephen Mattoon, in 1871, Mattoon purchased land on Beatties Ford Road across from campus so that teachers could build homes close to their work. Over the next 45 years, Mattoon sold plots of the land to Black people who wanted to settle near the college. That began Biddleville, which remains Charlotte’s oldest surviving Black neighborhood. Mattoon’s purchase helped begin growth and development on Charlotte’s West Side.

In the 1890s, when Biddleville was an all-Black neighborhood, white residents lived nearby in a rural settlement called Seversville. This became a pattern in both the white and Black communities, as both groups chose to settle near JCSU’s campus. As Charlotte expanded and began annexing land, the suburbs reached both Biddleville and Seversville, where both races were welcomed. It wasn’t until after World War II that this became known as the Black part of town. The West Side of Charlotte continued to grow as the suburb of Western Heights appeared near JCSU.

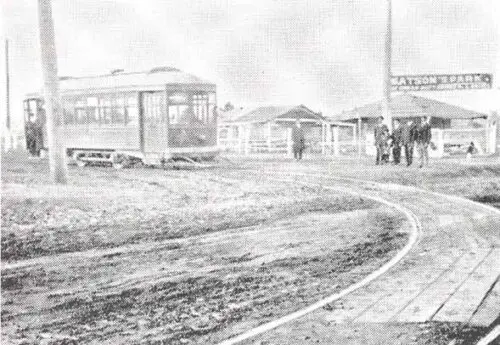

Western Heights is a suburban neighborhood that sprang up near JCSU and was initially open to both Black and white buyers. Part of what made Western Heights successful was its proximity to JCSU and the fact that it became a streetcar suburb, with tracks reaching it in 1903. Because of the things it has to offer, like Watson Park, which was the only park in Charlotte for Black people in 1915. Black elites began to live there and use the streetcars to commute to work. By the 1920s, white residents in Western Heights began to leave, making the neighborhood all-black.

At the same time Western Heights was beginning to grow so was Washington Heights. Washington Heights is yet another example of a neighborhood built near JCSU. In 1913, a group of white investors worked with a black businessman named C.H. Watson to plan the suburb. Washington Heights was named for Booker T. Washington, and several of the roads were named for famous African Americans. By 1931, 160 families, primarily Black middle-class families, lived in Washington Heights.

The advent of the streetcar in the 1910s helped spur the development of Charlotte’s West Side. As JCSU attracted people to the West Side, those people needed a way to commute to other parts of Charlotte. McCrorey Heights sprang up in 1912 and was started by Reverend H.L. McCrorey. McCrorey Heights was a community of 130 homes, that really developed between the 1950s and 60s where Black teachers, ministers, dentists, lawyers, and doctors lived comfortably. The residents of McCrorey Heights met within their homes to challenge the racially segregated status quo and the to establish new rights and freedoms for Black people.

In 1991, JCSU founded the Northwest Corridor Community Development Corporation (CDC), which helped stimulate new developments along Beatties Ford Road. The Northwest Corridor CDC worked to rebuild a shopping center in 1995. They built a new housing complex for senior citizens in 2000 and built townhouses in 2008.

Johnson C. Smith University was and is a valuable asset for all of Charlotte but has had a specific impact on the West Side. The Beatties Ford corridor, which grew because of Johnson C. Smith, is part of the city’s Corridors of Charlotte program, which supports six underinvested areas in Charlotte. The Corridors of Charlotte program seeks to create equitable entrepreneurship, beautify the corridor, expand public transit, and create more gathering spaces and opportunities within the Beatties Ford.