West Charlotte High School is the only high school left in Charlotte that was created to educate Black students. It is still actively serving its community as a high school. It was on Charlotte’s west side at 1415 Beatties Ford Road. How did integration and busing affect this beloved school?

Early in the 20th century, most of Charlotte’s African American population lived in Second Ward. By the 1920s, the city’s population had exploded to 46,338 from 18,091 in 1900. The city had grown past its original four wards. Charlotte’s African American residents began to look to the west side, where a network of neighborhoods surrounded historically Black Johnson C. Smith University (JCSU). The growth of the westside necessitated a need for a Black public high school.

Mecklenburg County had a $485,000, 17 school project funded by the Public Works Administration (PWA). The PWA was a New Deal program created to bolster the economy and provide employment relief during the Great Depression. West Charlotte High School, the largest school in the construction project, was underway by 1934.

In 1938, West Charlotte High School opened its doors at 1415 Beatties Ford Road in a two-story brick building with 17 classrooms, chemistry, general science, and physics labs, a library, and administration offices. The first principal was Clinton L. Blake, who oversaw 398 students in grades seven through ten and fourteen teachers.

In just a few short years, the school had grown, adding grades eleven and twelve in 1944. Blake ensured that the school had a rigorous college preparatory curriculum that promoted students’ growth and prepared them to be productive members of society.

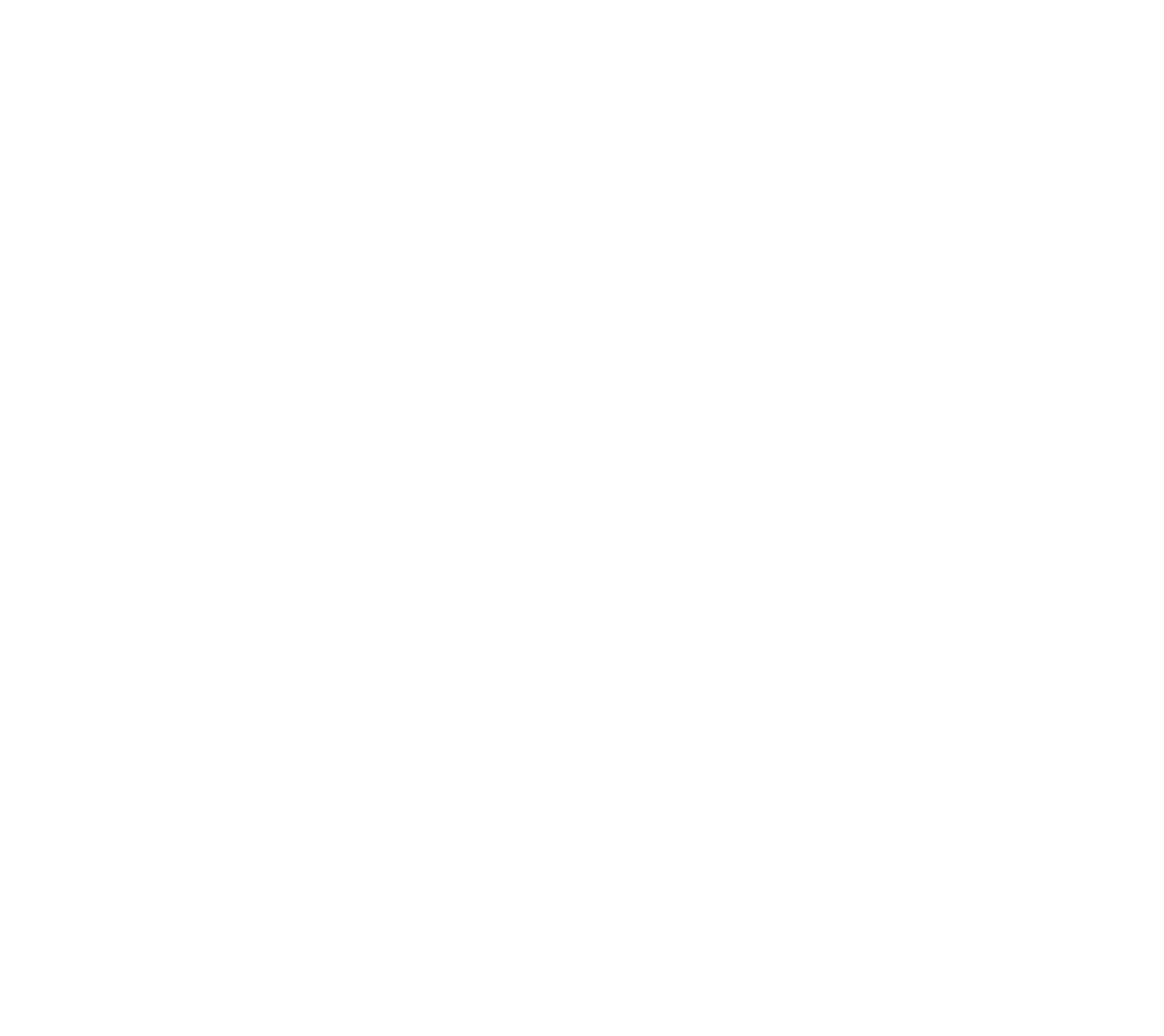

Roughly a decade later, in 1954, West Charlotte High School moved to its current location at 2219 Senior Drive. Principal Clinton remained at the helm and had grown to 800 students with 31 teachers. In the 1950s and ’60s, West Charlotte added a vocational curriculum that included driver education, commercial architecture, distributive education, mechanical drawing, industrial arts, printing, cosmetology, tailoring, home economics, and photography. A business education program was also added, which included courses in marketing, shorthand, typing, data processing, and bookkeeping.

The landmark 1954 case of Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka found racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. The decision to desegregate came in 1954, but most Charlotte schools didn’t desegregate until over a decade later. The faculty at West Charlotte integrated before the students did. By the mid-1960s, less than 5% of African American children attended desegregated schools.

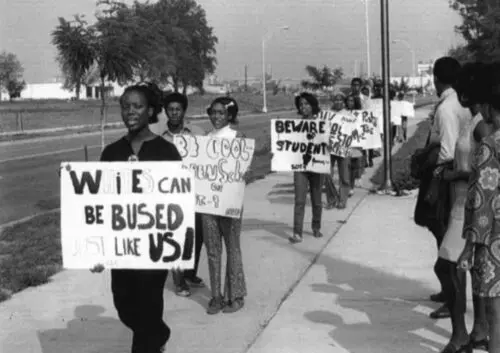

A 1969 federal ruling mandated that every Charlotte school had to have 70% white students and 30% Black students to match the system-wide demographic. That ruling, coupled with the Swann vs. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education case in 1971, gave federal judges the power to require the school district to fully integrate, even if this meant creating a busing system. As Charlotte rolled out its new busing system, it was met with mixed reactions from both the Black and white communities. But it did succeed in fully integrating Charlotte’s schools.

Charlotte became a beacon for school integration beginning in the mid-1970s, and West Charlotte High School was the school leading the charge. At the time, West Charlotte was the only historically black high school still operating in the Queen City, so it was very difficult to determine which white children would attend integrated schools. A group of affluent white parents decided to send their children on buses to West Charlotte, which served as a catalyst for busing.

Integration was not an easy change for West Charlotte’s black teachers and students as the school had a reputation for being an elite Black school and an important fixture on Charlotte’s west side. But the school welcomed white students. Many white students came from affluent homes with powerful parents, meaning West Charlotte received more financial support, enhancing its curriculum and materials. Extracurricular programming also helped ease the tension and growing pains associated with integration, as extracurricular activities helped unite students. By the mid-1970s, West Charlotte High and Charlotte were seen nationally as an example of integration. Leaders and students across the nation came to observe and see how Charlotte had made such great strides.

West Charlotte High School was integrated, but by the 1980s, Charlotte became more segregated by race and income. Between Reagan’s economic policies, decreased social spending, tax cuts, and deregulation, which benefited the well-off and harmed the poor. Developers built housing for mostly affluent white residents in the suburbs, resulting in white flight from urban neighborhoods and schools. Meanwhile, low-income housing that Black residents used was mainly clustered in the city’s center. Those changes made integration much more difficult as West Charlotte’s Black and white students now lived much further from one another.

CMS began reassigning students to schools primarily based on where they live; because low-income housing was concentrated in the heart of the city, those schools received less funding. In 1999, a federal judge ordered the city to stop using race in school assignments and busing stopped. When busing stopped, West Charlotte High School resegregated.

In 2022, West Charlotte High School opened a new 330,000–square–foot building with three levels. The new building cost $105 million dollars and replaced the school’s former building that was seventy years old. Today, West Charlotte High School has 98.3% minority enrollment, with less than two percent of the student body being white.