The Charlotte Woman’s Club (CWC) is the oldest civic organization in Charlotte, North Carolina. In its heyday, the CWC had power and influence. How did the CWC wield its power? What causes did it advocate for?

Twenty-five years before the Club occupied its long-term home at 1001 E. Morehead Street, a small group of women began the organization’s journey. The CWC started in the home of Mrs. Brevard Springs on South Boulevard in 1899 when six women gathered to create the Charlotte Mother’s Club. This group continued to meet until 1901 when it changed its name to the Charlotte Woman’s Club. At that time, the CWC invited 25 more women to join.

In the late 19th century, when the CWC was founded, the way women were viewed in society was beginning to change. The women’s club movement was sweeping the nation, and it was a highly racially segregated space for women of means. The movement empowered women and established that they had a moral responsibility to aid in transforming public policy.

Women at that time were usually bound to the domestic sphere. They were expected to be homemakers and care for children, while men worked outside the home in the public sphere. Women who participated in activities, including jobs, outside the home were seen as less feminine. Many women of color and white women of less economic privilege were already working in mills, retail, and, in the case of Black women, the homes of middle- and upper-class white people. The CWC was composed of white women and followed the lead of the highly segregated society in which it operated. Wealthier Black women were left to form their own women’s clubs; for example, nearby Salisbury had the Colored Women’s Civic League (CWCL).

One of the early presidents of the CWC, Mrs. F.C. Abbot, advised the Club to go outside of the domestic sphere by getting involved in civic activities for the sake of children. She encouraged the CWC to advocate for health laws, school matters, and social influences. Members of the CWC took Abbot’s words as a charge. By 1905, the Club had 86 members and held meetings twice a month at the Carnegie Library on North Tryon Street. It continued to grow, advocating for public and social issues. The CWC joined the North Carolina Federation of Women’s Clubs in 1903, and later, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs in 1908. In 1910, the CWC advocated for public playgrounds and improving those spaces in large cities like Charlotte.

By 1919, according to Glenda Gilmore’s Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896-1920, the CWC was discussing race relations, starting with “the servant problem” and reading books on the subject. Gilmore notes that they did not only discuss on their own, but they also invited “Negro Race Leaders.” Many of the white women in the CWC did not interact with Black women outside of those that worked as domestic servants in their homes.

However, as white women began to gain more power in social organizations and public education in the first two decades of the 20th century, they began to wield their newfound influence. White and Black women began to sometimes work together on individual initiatives through careful and often unequal political alliances. This was an important step for Charlotte because white women controlled access to resources that Black women needed to improve their own communities.

One of the first major points of interaction between the CWC and CWCL was in 1920, when the two groups worked together to organize citywide cleanup days. Work in public health, something that affected everyone regardless of race, provided a common place of interest. Also, in 1920, the CWC organized health clinics that employed both Black and white nurses. Both groups’ salaries were partially supplemented by the Charlotte Woman’s League.

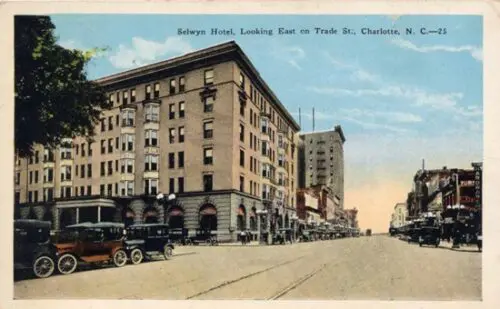

By the 1920s, there were more than 500 members, necessitating the CWC’s first clubhouse. In December of 1920, the Club purchased the home of A.J. Draper on Elizabeth Avenue. They sold their clubhouse on Elizabeth Avenue just two years after buying it. In the interim, they met in the ballroom of Selwyn Hotel on W. Trade Street. In January of 1923, Edward Dilworth Latta, Charlotte industrialist, and creator and namesake of the Dilworth neighborhood. Latta offered the CWC a lot to build their new clubhouse on the corner of Morehead Street and Dilworth Road. The only stipulation was that the clubhouse could cost no less than $50,000.,

The new clubhouse, designed by architect C.H. Hook, was built and opened to the public on May 22, 1924, at 1001 E. Morehead Street in Charlotte, North Carolina. The CWC used the clubhouse until it sold the property in 2008.

The Charlotte Woman’s Club wielded considerable power in its day, and many Charlotte business leaders supported the CWC. Business leaders like D.A. Tompkins, the owner of the Charlotte Observer, made several donations to the organization. Latta donated the land for their Morehead Avenue clubhouse, and James B. Duke also made financial contributions to the CWC. All of them were leading businessmen in Charlotte, and all of them supported the CWC because members shared their belief that technology and science could better life for Charlotteans.

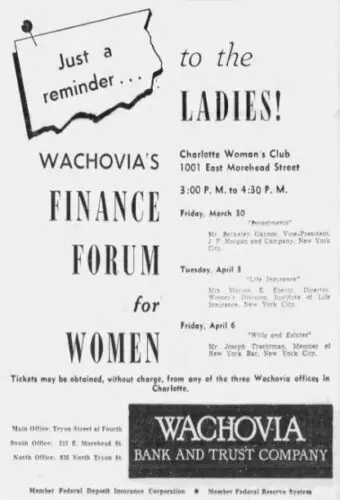

Throughout its existence, the CWC has lent its platform and influence to various causes. For example, in 1923, the Club was called upon by Reverend Irving Richardson to use its power to reform newspapers. Richardson believed that newspapers gave too much ink to crime and not enough ink to promote health and life. In 1951, the CWC held the Wachovia Finance Forum for Women. The Forum was a series of 90-minute talks on financial literacy topics like investments, life insurance, and wills and estates, all given by experts in those fields.

In 1970, the CWC publicly opposed forced busing, going as far as to write a resolution. Their resolution listed the following reasons for opposition: forced busing prohibits freedom of choice, it destroys the neighborhood school concept and discourages parental participation, they argued it was time-consuming and presented a safety and health hazard to students and their families, and lastly, it argued that forced busing might not be a genuinely democratic way to live. In 1978, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmark Commission designated the building a historic landmark.

The CWC raised money via a fashion show and luncheon to provide scholarships for nursing students at Presbyterian Hospital and Central Piedmont Community College and repair projects at their clubhouse.

Throughout its history, the CWC established the city’s first kindergarten; they organized the PTA, YWCA, and the Traveler’s Aid in Charlotte. After selling the clubhouse on Morehead Street in 2008, the CWC met in its members’ homes or community spaces. Today, the Charlotte Woman’s Club is still active in the community by putting on programs and projects like Shoe Closet, a project that helps provide shoes and socks for children in the community. They also do ground cleanup projects at different sites around Mecklenburg County like the James K. Polk State Historic Site.