Charlotte has been confronted with many issues that it has had to overcome to grow, attract businesses, and become a major city. Those challenges have required complex and interesting solutions. Vest Station, located at 900 Beatties Ford Road in McCrorey Heights, is one of those solutions.

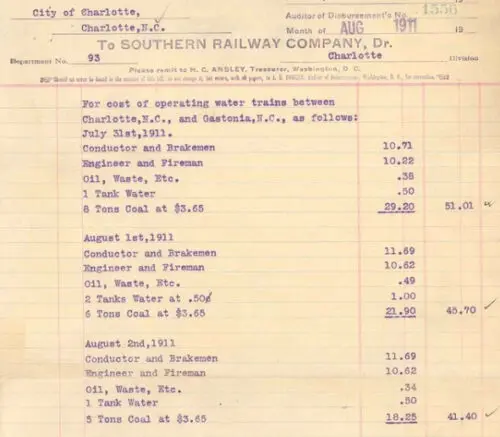

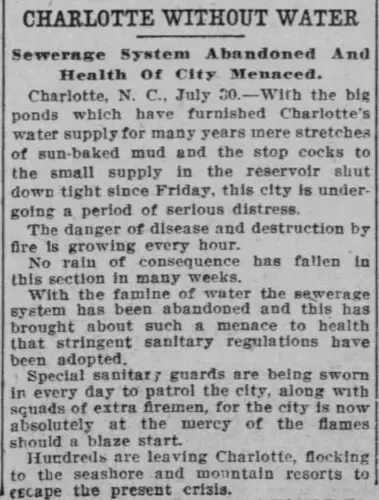

In 1911, Charlotte was stricken with drought as Charlotte’s main water reservoir, Big Sugaw Creek (now called Irwin Creek), was drying up. This was the worst drought Charlotte had seen in 50 years, peaking in July 1911. There was so little water left that sewers were only turned on when they needed to be flushed. Things got so bad that police were removing sprinkler systems from people’s yards and confiscating garden hoses. City officials began shipping water via railroads from neighboring cities.

Charlotte has always been a city that is open for business; as such, city officials were concerned about how the water crisis would affect the city’s reputation. Other cities like Baltimore and New York City ran disparaging stories in their newspapers about Charlotte’s water crisis.

Given the inconvenience and the health concerns caused by the crisis, the city officials acted quickly. Charlotteans gladly opened their wallets to contribute to the $815,000 ($26 million in 2024) bond it would take to fund a solution. By 1912, city officials had adopted a two-step process to fix this issue. Step one was the creation of the Catawba Pump Station a piping and pumping system connected to the Catawba River. Step one alleviated the water supply problem.

Step two was Vest Station, a water treatment plant that Charlotte desperately needed. The Catawba Pump Station was a band-aid for a larger issue. By 1918, Charlotte had a population of 50,000. It was growing rapidly, and if city officials wanted it to continue to accommodate population and business growth, they needed a water treatment plant. Water treatment plants are responsible for collecting, treating, and distributing water to the city. In 1922, construction on Vest Station started.

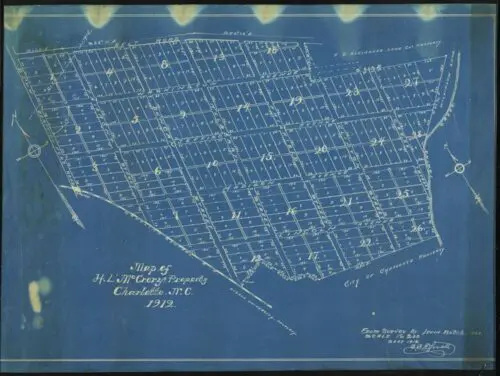

Vest Station was constructed in McCrorey Heights, a neighborhood created by H.L. McCrorey for Black residents in 1912. near Johnson C. Smith University (JCSU). McCrorey Heights was selected because of its high elevation and proximity to existing water mains. This land was a prime location to collect water from existing water mains. At the time, the land was undeveloped. McCrorey was the president of Biddle University (now Johnson C. Smith University), and he owned the land and planned to use it for future African-American development. After a lengthy and complex eminent domain process that, according to QCity Metro, Charlotte Water has since been regarded as a “complex, conceivably unfair legal process” the City of Charlotte acquired the land from McCrorey.

Vest Station was completed in 1924. It is an art deco modern-style building that was made of concrete which was very common in industrial buildings in the 1920s. At the time of its opening, Vest Station was the largest fully–equipped, modern water treatment and storage facility in North Carolina. It is named after W.E. Vest, the general superintendent of the Charlotte Water Department for more than 30 years. In 1924, Vest Station could treat 8.3 million gallons daily and store 3 million gallons of clean water. By 1930, according to the U.S. Census, Charlotte’s population had reached 91,264, and by 1940, the city had a population of over 100,000.

To keep up with the city’s growth, a series of upgrades to Vest Station were made between 1936 and 1949. The facility could hold 25 million gallons of water and 12 million gallons of clean water. In 1949, Charlotte became the first city to use fluoridation in the Southeastern United States. In 1989, Charlotte was given a “Certificate of Recognition” by the National Institute of Dental Research.

After over 100 years of service, Vest Station still serves as an important part of Charlotte’s water treatment. The station’s interior still reflects its 1920s–style architecture, with arched ceilings, marble control tables, and red clay tiles. The station can still be operated manually, which is helpful in an emergency, and it has been continuously updated to be just as technologically advanced as any new water treatment plant.