When we think of Charlotte today, we usually think of skyscrapers, banks, and breweries: a city open for business and ripe for growth and expansion. But it wasn’t always that way. At the turn of the twentieth century, it was still a relatively small city. With the construction of Camp Greene during World War I, Charlotte’s population doubled. Camp Greene was located between Wilkinson Boulevard and Tuckaseegee Road in Charlotte, North Carolina, one mile west of Uptown.

Camp Greene was a United States Army training facility where the 3rd and 4th Infantry Divisions were first organized and trained. Camp Greene was created in direct response to World War I. The Allied Powers (Great Britain, France, Russia, and Italy) and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire) had fought to a stalemate by 1917. Sensing that they needed to turn the tide of war, the Allied Powers made a desperate plea to President Woodrow Wilson for aid. The United States joined the Allied Powers and officially declared war on the German Empire on April 6, 1917.

The United States only had 100,000 full-time soldiers at the time, but thousands more were needed to end the Great War. Before the United States Army could begin recruiting, they needed a place to train soldiers. The Army planned to build 32 facilities across the county. Charlotte’s business community and leaders saw this as an incredible opportunity. A training facility meant the creation of new jobs, money, and a new level of prominence for Charlotte.

This charge was led by David Ovens, the President of the Chamber of Commerce. Ovens and other business leaders devised a pitch to the United States government explaining why Charlotte should be selected for a training facility. They argued that Charlotte had the infrastructure to accommodate a camp, the land, moderate weather patterns, and access to a major rail line, which made transporting soldiers and munitions much easier. Their efforts to attract outside government and business entities to Charlotte were part of a long tradition in the city that continues today.

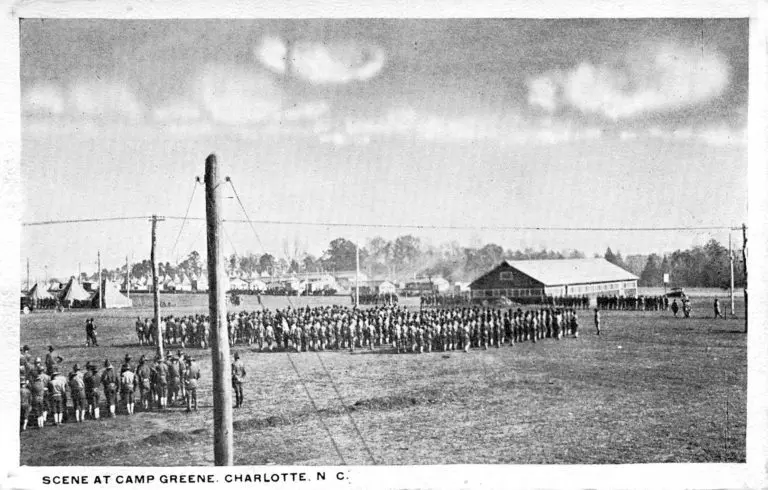

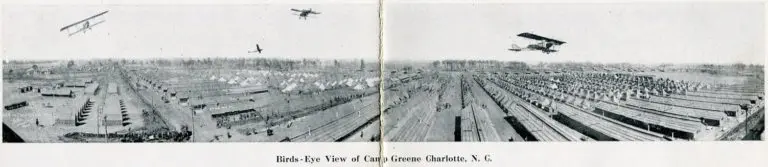

The United States Army sent Major General Leonard Wood, the commander of the Southeastern Division of the Army, to visit the proposed site on July 5, 1917. Maj. Gen. Wood liked the proposed site, and in just six weeks the camp was ready with recruits arriving on September 6, 1917. Camp Greene was over 8,000 acres of land and had everything needed to run efficiently and adequately prepare soldiers for combat.

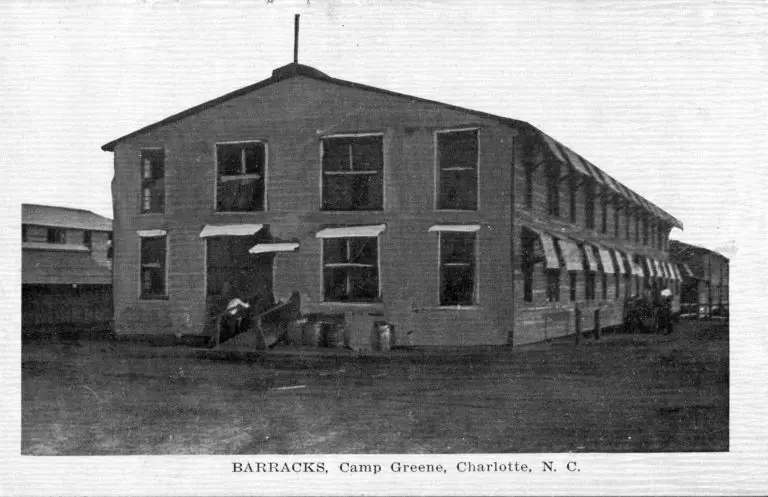

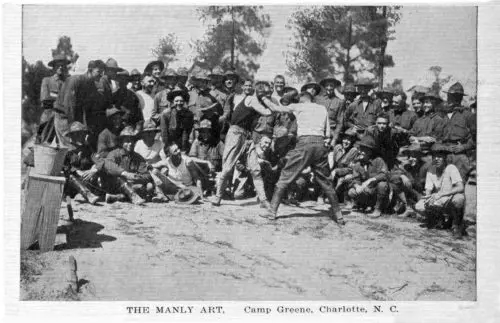

There were wooden barracks and tents for housing, a post office, a bakery, an airfield, a rifle range, and a large hospital. The Army would eventually push Charlotte leaders to expand or lose the facility. The Chamber of Commerce raised enough money to accommodate the Army’s demands to add an artillery range and airfield to train pilots. At its peak, Camp Greene saw more than 60,000 soldiers live on base. The sheer number of soldiers passing through Charlotte created more avenues for businesses to provide goods and services, which drew even more people to Charlotte. Roughly 8,200 building permits were submitted in three to four years after Camp Greene. Many Charlotte businesses, like segregated Lakewood Park, benefited from Camp Greene’s troops as they would use their leave time to enjoy the park and its roller coaster, bowling alley, and many other activities.

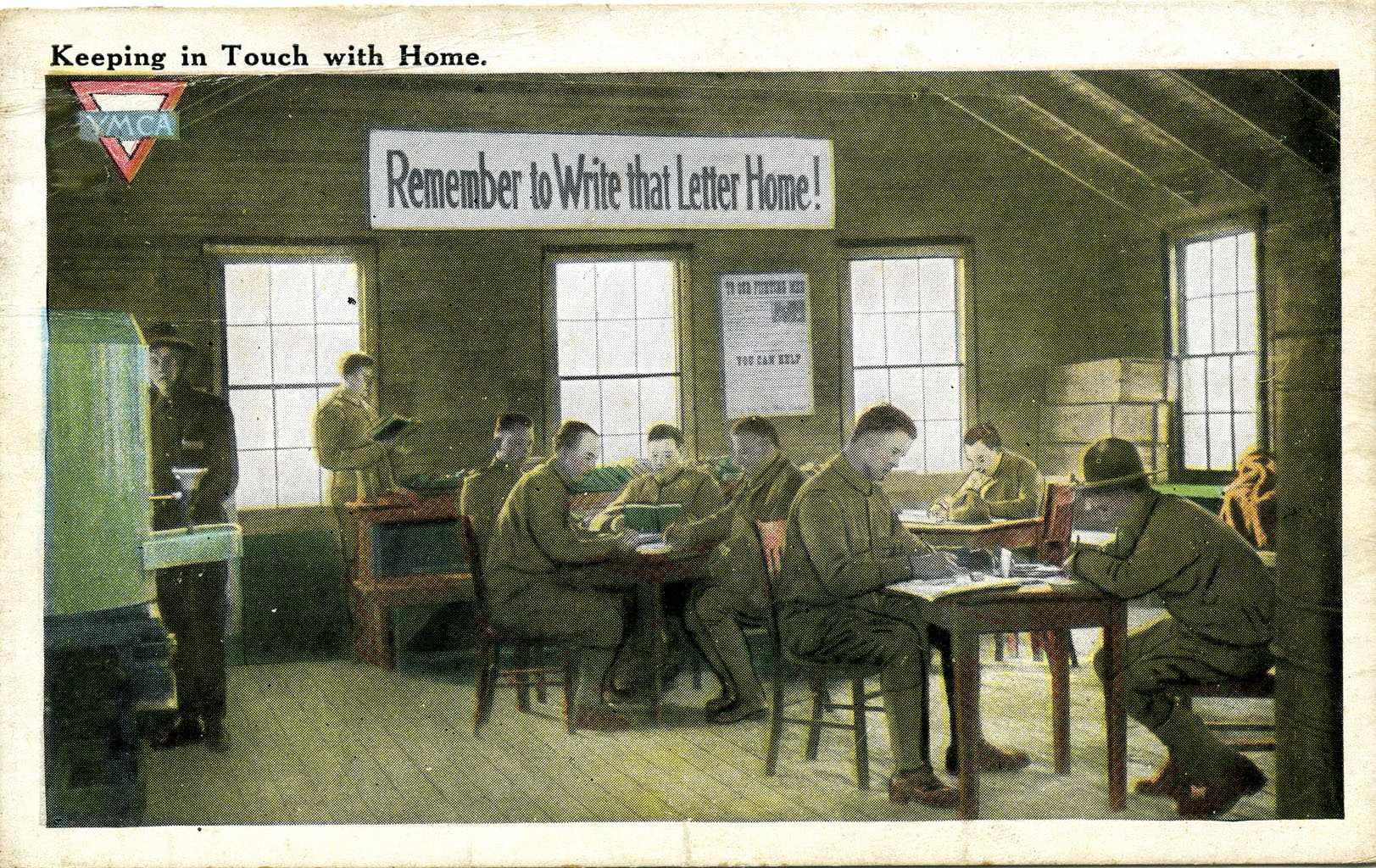

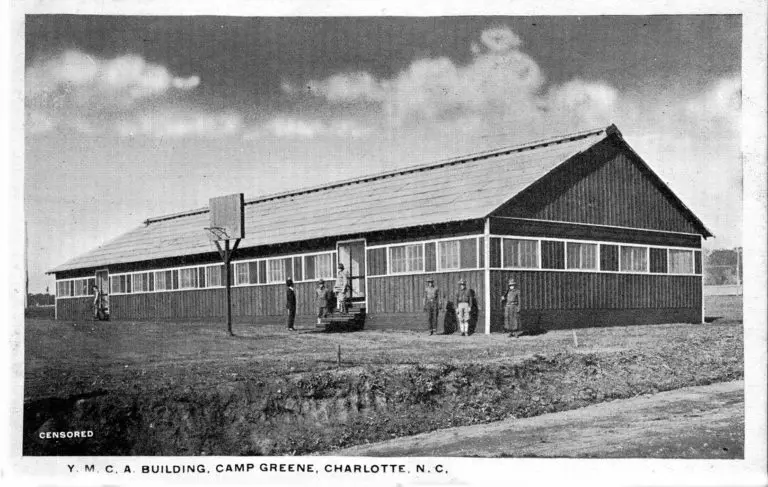

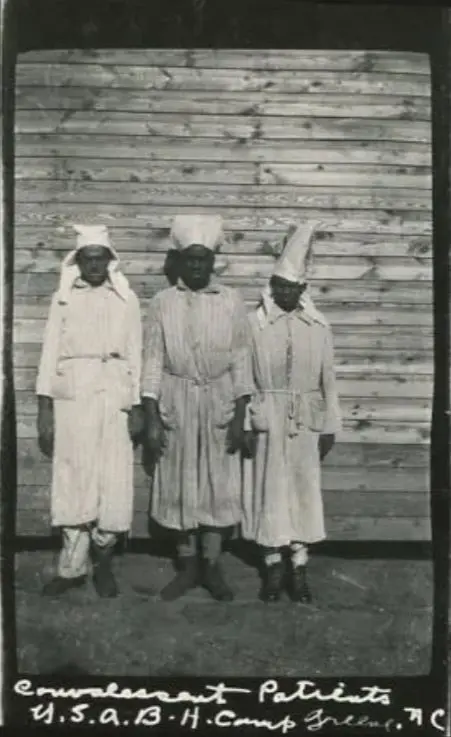

Most of the troops sent to Camp Greene were from New England and western states, with troops from Massachusetts constituting the largest number. Some of the troops had recently immigrated to the United States and barely spoke English, taking lessons at the base’s YMCA. At one point, Camp Greene had 14,000 black troops from Massachusetts and Connecticut. Black troops at Camp Greene were segregated and treated poorly. They served in labor or supply units, with high amounts of physical labor and little to no combat training. Black troops typically slept in tents instead of the barracks occupied by their white counterparts. Black troops also received segregated healthcare and had a higher mortality rate than white soldiers. White doctors did not know how to treat Black people and racistly believed that Black people had weaker immune systems than white people.

As the Great War ended in the fall of 1918, another enemy began to rear its head. The Influenza virus had come to the U.S. In October of 1918, all soldiers, officers, and staff were placed under quarantine to control the outbreak. Any soldier that was able to be shipped overseas was sent. The camp was largely empty, except for some Black soldiers. Almost 300 people died of influenza at Camp Greene by the outbreak’s end.

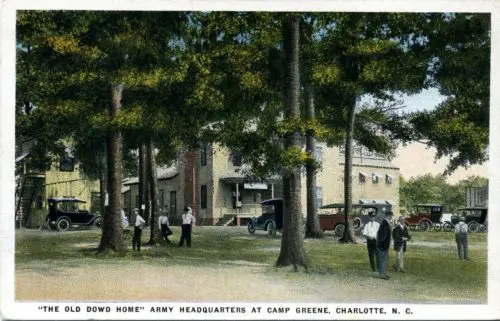

World War I ended on November 11, 1918, and Camp Greene was torn down and returned for civilian use. The only original structure left at Camp Greene is the James C. Dowd House at 2216 Monument Street, which served as a headquarters for the Army on site. Even with Camp Greene gone, many people who came to live and work there remained in Charlotte. Camp Greene was vital to Charlotte’s growth and provided an early spark for an up-and-coming boomtown.