When it opened in 1929, Dr. Charles L. Sifford Golf Course was originally called Bonnie Brae, which means “pleasant hill” in Gaelic. But things were anything but pleasant when sixteen Black golfers filed a petition for the right to play at Bonnie Brae, a whites-only golf course in Charlotte.

On December 12 and 13, 1951, sixteen African –Americans were denied access to play at Bonnie Brae Golf Course, which was at the time a whites-only golf course owned by the City of Charlotte. A little over a week later, on December 21, 1951, those sixteen golfers filed a petition against the city, the Charlotte Parks and Recreation Commission, and the superintendent of Parks and Recreation, and the golf course manager.

The petitioners believed that as tax-paying citizens of Charlotte, they and all African Americans had the right to use the golf course. The petition also stated that the answer was considered no if it went unanswered after fifteen days.

Among the petitioners were some of the most respected members of Charlotte’s Black community. Charles W. Leeper was a respected barber, Henry M. Isely was a pharmacist, and Robert H. Green was a doctor. Rudolph Wyche was the cousin of Thomas A. Wyche, the legal counsel for Charlotte’s NAACP chapter. Thomas Wyche and Spottswood Robinson, the NAACP Southeast Regional legal counsel, represented the petitioners. Their main argument was that Bonnie Brae was the only city-owned, taxpayer-funded golf course in Charlotte, and the city could not provide “separate but equal” facilities for Black golfers. The petitioners also had full support from the Charlotte NAACP chapter, led by Kelly Alexander, Sr.

The Charlotte Parks and Recreation Commission denied the petition and based their argument on the “reverter clause” in the city’s contract with Osmond Barringer, F.C. Abbott, and W.P. Shore, the men who had donated much of the land used for the golf course. The clause stipulated that the land could only be used by white residents. If this clause was violated, the land would be returned to the original owners. Barringer, who was a white supremacist, threatened to invoke the clause. He said that “Negroes are not ready for this step yet.” Barringer’s involvement meant that this would be a prolonged legal battle.

The case was brought to trial on December 4, 1956, before the Mecklenburg County Superior Court and Judge Susie Sharp. Robinson and Wyche represented the petitioners while John Shaw, a city attorney, argued for the defendants. Shaw argued that the reverter clause might mean that the land and, therefore, the golf course, would be lost to all golfers in Charlotte. Shaw proposed that the city could use eminent domain to prevent ownership reverting.

Judge Sharp asked the petitioners if a compromise would work in which Bonnie Brae would remain whites-only while efforts were made to build or buy a golf course for Black golfers. The petitioners rejected the compromise and would only accept playing at Bonnie Brae. Robinson acknowledged that refusing to compromise could mean the end of the golf course for all golfers, regardless of race.

This quick trial lasted one day. Judge Sharp ordered that the Charlotte Parks and Recreation Commission could no longer deny African Americans the right to play at Bonnie Brae. The Commission was given 90 days to resolve its dealings with Osmond Barringer. On January 9, 1957, James Otis Williams became the first black golfer to play at Bonnie Brae Golf Course.

Bonnie Brae was originally 18 holes, but the back nine was lost to I-77 when it was completed in 1976. The course only having nine holes meant fewer people played on it as it was no longer a regulation golf course. The remaining nine holes greatly deteriorated over time. In the early 1970s, there was a string of robberies and even a murder that happened on the course causing a drop in attendance. The robberies and the murder resulted in a fence being built around the course in hopes of making golfers feel safer and drive attendance back up. In the 1970s, the name of the course was changed to Revolution Park Golf Course.

As time went on golfers returned to the golf course. In the 1980s, the golf course advertised their tee times in the Charlotte Observer and even gave coupons. The course sponsored charity tournaments like Captain’s Choice that raised money for the Special Olympics.

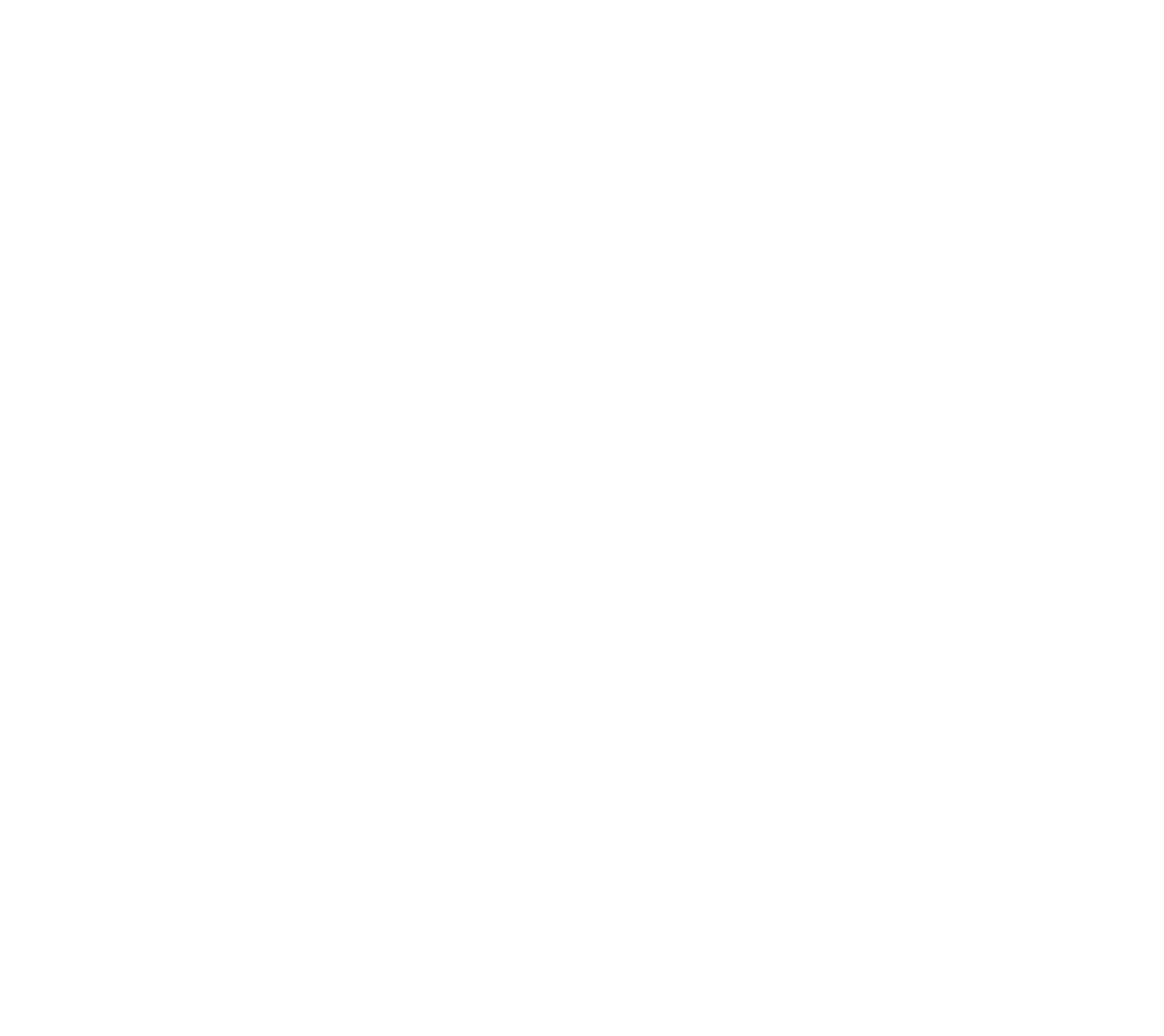

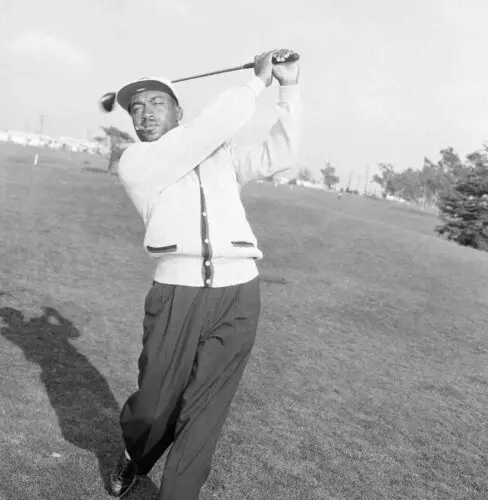

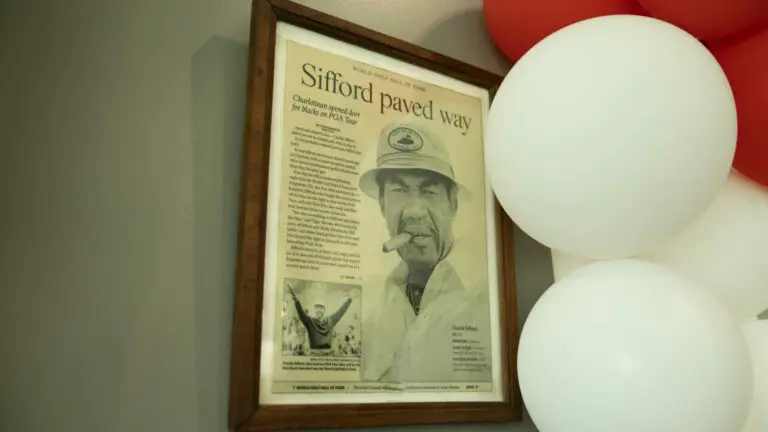

In 2010, the golf course was renovated and renamed to honor Dr. Charles L. Sifford. Sifford was originally from Charlotte; he was introduced to golf as a teen when he worked as a caddy at Carolina Country Club. He served in World War II until he was honorably discharged in 1946, when he resumed his pursuit of a golf career.

Sifford was the first African American to play on the PGA Tour in 1961, winning twice in 1967 and again in 1969. Today, the Dr. Charles Sifford Golf Course is consistently rated one of the best golf courses in Charlotte.