Good Samaritan Hospital is affectionally remembered by its patients as Good Sam, the first privately funded hospital in North Carolina built specifically to care for Black people. The original hospital was located at 411 W. Hill Street in Charlotte’s Third Ward neighborhood. Today, if you were to drive through or walk around Third Ward, all that remains of Good Samaritan Hospital is the historic marker on South Graham Street. Good Samaritan was torn down in 1996 to make room for Bank of America Stadium.

The cornerstone for Good Samaritan Hospital was laid in 1888, and the hospital was completed in 1891 through funding raised by St. Peter’s Episcopal Church and its parishioners. In its early years, it received minimal funding, so the hospital offered the best services it could given its resources. The hospital was initially created to house twenty patients, with three doctors on staff and a matron. During the first six months it was open, the hospital staff only saw 13 patients for care. Initially, the Black community faced Good Samaritan Hospital with a level of distrust. People were reluctant to get the care they needed due to rumors they heard about hospitals. For example, one patient was brought in kicking and screaming by police officers. He had heard that people were “carved up with butcher knives in hospitals,” so he did not want to go into the hospital.

The Good Samaritan Hospital also educated future nurses with its first graduating class in 1905. The School of Nursing was a success, and it went on to train hundreds of Black nurses. Good Sam was also a place where Black doctors and nurses could gain experience and hone their craft. The entire staff was put to the test in 1911 when a trainwreck near Hamlet, North Carolina brought 81 Black patients to the hospital. All the physicians in the city came to Good Sam to care for the patients, saving all but three patients from dying of their injuries. The level of care provided in that crisis secured Good Sam a reputation as a legitimate healthcare provider and brought it the prestige it deserved. This reputation helped secure funding for the growth of Good Samaritan’s facilities.

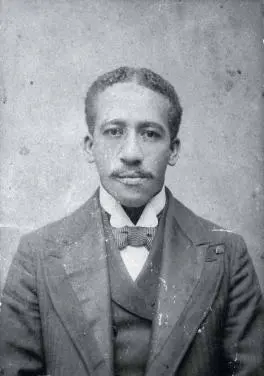

Good Sam’s new level of prestige did not prevent it from being the site of one of Charlotte’s most disturbing and horrendous racial incidents: the only documented lynching in the city’s history. On August 26, 1913, Joe McNeely was involved in a shootout with a white police officer, resulting in both being wounded. McNeely was taken to Good Samaritan for care, where a white mob arrived, drug him from the hospital, and shot him to death. No one was ever arrested and prosecuted for his murder. The white mob had violated Joe McNeely and an important space of health and healing for African Americans in the city.

Despite being the site of such a heinous crime, Good Sam was able to grow. In 1925, Good Sam built an addition in response to an influx of people to the Charlotte area after World War I. The hospital would continue to grow with additions added in 1937. Even as it expanded, Good Sam was proof separate was never equal. Good Samaritan Hospital lacked essential tools like an X-ray department or pathology lab, making the hospital staff’s job much more difficult. Faced with these resource challenges, generations of doctors and nurses like Thereasea Elder took excellent care of Charlotte’s Black community and the community at large. Thereasea Elder was the first Black public health nurse in Charlotte.

Good Sam was exclusively governed by a group of women until 1947, when the hospital organized an Executive Board comprised of two people from each Episcopal parish church. Over the next decade, it became challenging for the parish churches to keep up with the growing needs of Good Sam, as the hospital provided care for all of Charlotte and the surrounding area’s Black population. The progress of the Civil Rights Movement, particularly the successful work of Dr. Reginald Hawkins and others to desegregate Charlotte’s white hospitals, led to the further decline of Good Sam.

In 1961, Good Samaritan Hospital was sold to the City of Charlotte for one dollar and was renamed Charlotte Community Hospital. This new hospital was racially integrated. Charlotte Community Hospital closed its doors in 1982 and was remodeled and converted into Magnolia’s Rest Home. In 1996, Magnolia’s was closed and torn down so Bank of America Stadium could be built.