Today, Lake Norman is an excellent destination for people who love boating, fishing, and hiking along with casual monster hunters on the hunt for the Lake Norman Monster. Some may find it hard to believe that the 32,000-acre lake was once farmland, mill villages, and other small communities. When thinking of Lake Norman, we don’t often think about the people who lost their homes, jobs, and livelihoods so it could be created. This was the human cost of both growing a company to meet the demands of increasing energy consumption.

Although Lake Norman did not exist until 1963, Duke Power (now Duke Energy) had been damming the Catawba River to build hydroelectric plants for years. The process was simple: dam the Catawba River to create more hydroelectric power for a society that was technologically advancing at a fast pace. New home appliances and air conditioning meant homes needed more energy now than ever. Post-World War II prosperity meant corporations like Duke Power grew rapidly, and its revenue doubled over the next decade.

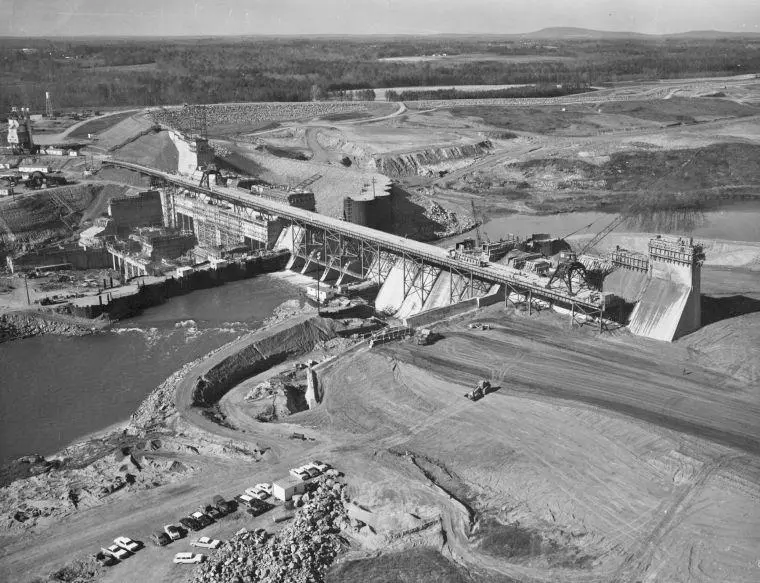

Duke Power had created six lakes on the Catawba. But creating a massive lake like Lake Norman requires a massive dam. Cowan’s Ford Dam was the largest and most ambitious damming project Duke Power had attempted on the Catawba River. Lake Norman is the largest artificial lake created by Duke Power, with over 500 miles of shoreline. Cowan’s Ford Dam is 130 feet high and over a mile long, while Lake Norman is 32,000 acres spanning four counties: Iredell, Catawba, Lincoln, and Mecklenburg. Its original purpose was to provide more power. As time progressed, it became a source of drinking water for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg area and a beloved recreational location.

Lake Norman is named after Norman A. Cocke, a former president of Duke Power. Duke had been purchasing land for the project since the 1920s, and by the 1950s, they had all the land needed to build the shoreline, lake, and dam. In the 1950s, buying land was difficult for Duke Power. Charlotte was growing, but Northern Mecklenburg County was still very rural, and getting farmers to sell their lands proved challenging. Some landowners wanted to drive the price of their land up, while others wanted to keep farming as that was their livelihood. At the time, nearly 2,000 people were living in the area. Duke had eminent domain but did not have to use that right.

Landowners typically had three options: sell all their land to Duke Power and move, sell their land and stay (Duke Power would lease the property to them for favorable rates), or sell the parts of the land that would be underwater and be left with lakefront property. Some farmers like Luther Cowan were against the lake and held out on giving up their land. Cowan refused to sell his land so that it could become the bottom of a lake. Duke Power eventually condemned his land and bought it at $200 per acre. His son repurchased the submerged land from Duke Power and was still paying $4.31 in taxes on the land as late as 1988 to keep it in his family.

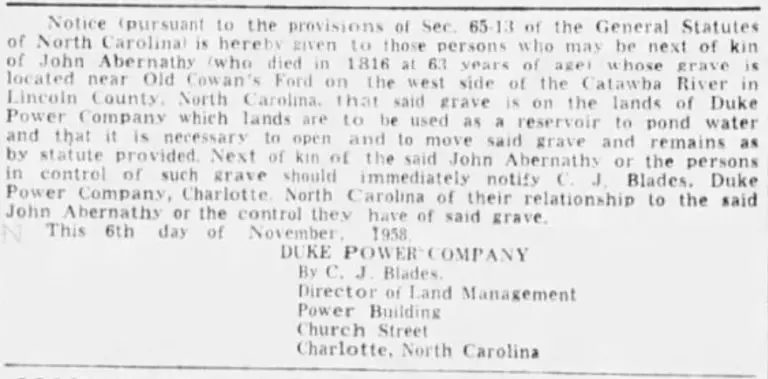

There were many hurdles surrounding the area Lake Norman intended to occupy. For this project to happen, the residents would have to move on their own accord or be displaced. There were also over a dozen churches, graveyards, and family burial plots. This was a place where generations of families lived. Each marked gravestone had to be removed, meaning the remains had to be relocated. Before remains relocation, the next of kin would have to give their permission. Finding next of kin was a tall order for people who had been dead for years. Duke Power ran ads in the Charlotte Observer looking for relatives. Occasionally, lake diggers would stumble across bones during construction.

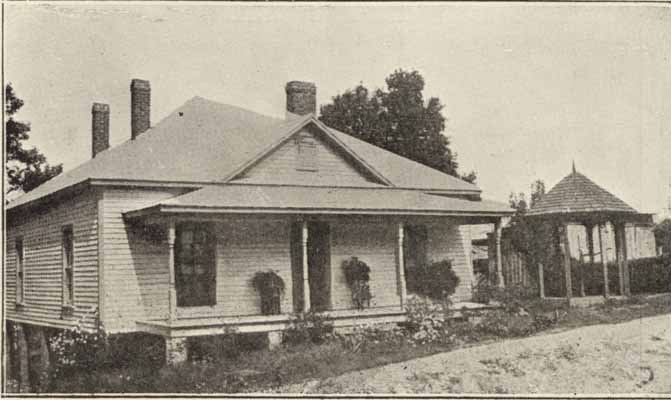

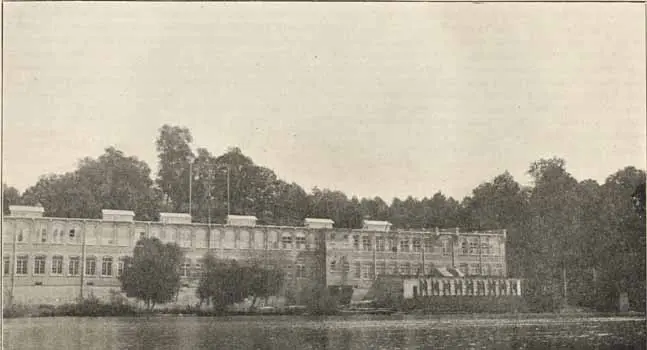

Farmers were not the only people to be displaced; mill workers and their families were facing displacement too. There were two operational mills in Iredell County: Long Island Mill and Village and East Monbo Mill and Village. When they closed in 1959, workers found it hard to get jobs. At the time, Iredell County was known for textiles and closing two mills resulted in displacement for many families. Duke Power told mill workers they could keep their homes if they could move them. So, some people literally picked their houses up, foundation and all, and moved. The ruins of Long Island Mill and Village can be found at the bottom of Lake Norman.

On September 1, 1960, the first bucket of concrete for Cowan’s Ford Dam was poured by Duke Power’s president, William B. McGuire. The dam was completed in 1962 and was capable of generating 262,000 kilowatts. In the spring of 1962, water began to flow, and Lake Norman was filled by June 1, 1963.

Ironically, the project that had displaced hundreds of residents initially had a tough time attracting people. The area lacked infrastructure in the form of roads, water, and sewage which couldn’t be supplemented by the surrounding towns support. It took almost an hour to get to Charlotte, and most of the lake bordered unincorporated territory. Lastly, Duke Power was interested in leasing, not in real estate at the time. Eventually, when Interstate 77 was paved, the development of Lake Norman and the surrounding area grew and blossomed into what we see today.

Lake Norman today has around 60 islands. It is 33.6 miles long with a maximum width of 9 miles and 520 miles of shoreline. It can reach a depth of 110 feet in some areas. From mill villages and farms, the area is now the most expensive lake market in NC and among the top five in the nation with its many multimillion-dollar properties. On the market most recently was a 12,000-square-foot property in Cornelius, featured in the 2006 film “Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby” purchased for over $6 million. Beloved community traditions are also now growing in popularity, from summer cooling spots in its public parks and beaches to the annuals Charlotte Dragon Boat Race & Asian Festival and the Lake Norman Lighted Christmas Boat Parade. However, it is not free of issues, and in recent years coal ash contamination has become an increasing concern in the Lake Norman area.