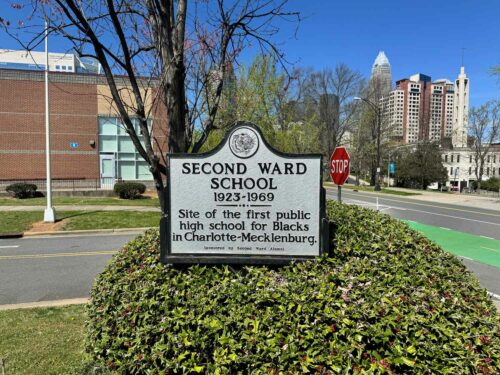

Second Ward High School was Queen City’s first public high school for African Americans. It opened in 1923 during a time of intense racial segregation and quickly became an integral part of Charlotte’s African American community. The school closed in 1969. Why did it close? What was Second Ward’s impact on the community, and how is it remembered?

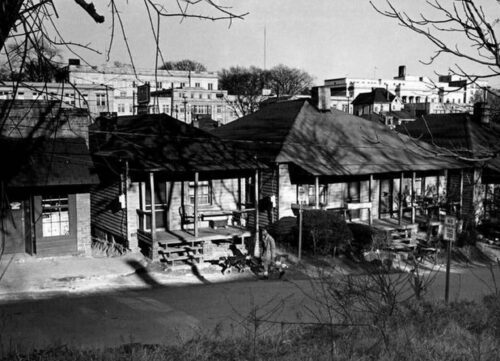

Second Ward High School was located in Second Ward’s Brooklyn neighborhood, a predominantly Black neighborhood that thrived from the early 1900s to the 1960s when the city used urban renewal to raze and displace its residents, businesses, and churches. Second Ward’s history dates back even further. Second Ward was not a desirable place to live in the 1860s because it was lower in elevation, at a time before indoor plumbing and storm sewers: it was a health hazard. Early maps of the region called the area Logtown because most homes were made of logs.

After Emancipation, Logtown, with its inexpensive housing, became a prime destination for freed people. As the area’s population grew, those living there frequently elected Black city councilmen throughout the late 19th century. By 1917, Second Ward was a predominantly Black ward except for Trade, Tryon, College, and parts of Fourth Street. It was around 1917 that the name Brooklyn emerged.

Brooklyn, in its prime, was a thriving neighborhood—a city within a city. There were schools, restaurants, businesses, shops, doctors, a library, and everything you would need. John Pettis, a 1967 graduate of Second Ward High School, said, ” We had everything in that community that we needed; it was like a city within a city.”

Second Ward High School was the first high school for Black students in the county. Before its existence, Black students had limited options for high school; they would have to go outside of Charlotte, attend a private school, or a church-run school. Second Ward High School students could take courses in practical home economics, auto repair skills, Latin, English, mathematics, history, and much more. The school attracted Black students from throughout Mecklenburg County.

The school quickly became a hub for Black families, as teachers inspired children and provided an excellent environment for students to learn despite facing challenges like overcrowding and unequal funding. Robert Parks, ’59 recalled that he had to attend class in shifts because the school was overcrowded. Students also remembered that they got hand-me-down athletic uniforms from the white high school Central High because they had a similar royal blue color. W.L. “Pop” Woodard ’67 said, “I never received a new textbook while I studied there; each one had been used for at least several years by white Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (CMS) students at other schools before being cast aside.” Even with those challenges, Second Ward High School was a phenomenal educational institution for the community.

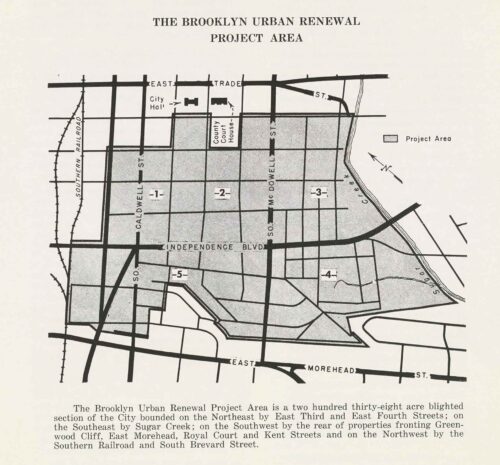

Despite its meaning to the community, Second Ward High School was closed in 1969, as various states across the country responded at different rates to the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision. So, in 1969, Second Ward High School and six other Black schools were closed. In the 1960s and 70s, the federal government was giving out billions of dollars for urban renewal projects across the country. That funding came under the guise of eliminating “slums” and “blighted” areas. Those areas were usually Black neighborhoods and Black people who were displaced by urban renewal and had their communities destroyed.

In 1967, voters supported a $35 million school bond thanks to the support of the Black residents, and $2 million of that bond was earmarked for renovations at Second Ward High School, which never happened. On three occasions that year, CMS endorsed a plan to keep the school at its existing location while modernizing the building. The school was meant to be renamed Metropolitan High School. By November of 1967, School Board Vice Chairman Harrison Belk asked if a new school should be built in a place with no students.

In 1970, Second Ward High School was demolished because the Board of CMS deemed the structure a hazard. Urban renewal and private demolition destroyed all of Brooklyn. Charlotte’s Government Plaza, hotel towers, office buildings, retail spaces, and luxury apartments rose from Brooklyn’s ashes. Only the school’s gymnasium still stands today on Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard. The gymnasium was designated a historic landmark by the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmark Commission.

Even though Second Ward High School was torn down, the alumni have not forgotten their school and what it means to be a tiger. The tiger mascot represented the power, courage, protection, and energy the school and education could give the community and students.

The Second Ward High School National Alumni Foundation began as the dream of three alumni: Cecelia Jackson Wilson, Louis C. Coleman, and Dr. Mildred Baxter-Davis. Holding their first meeting in 1980, after watching their school be torn down and Brooklyn be toppled, their goal was to create a permanent foundation to preserve the school’s memory and legacy. They preserve and collect trophies, yearbooks, newspapers, photos, and other memorabilia that tell the story of the school and neighborhood.

More than $176 million of a new CMS $2.5 billion bond is expected to create Second Ward Medical and Technology High School. CMS is looking to rebuild Second Ward High School, focusing on medicine and technology at the exact location of the original school. The school is expected to accommodate around 2,000 students. Alumni are hopeful that this project will come to fruition. Grace Hoey, ’55 said, “We are working hard so that Second Ward will not be forgotten. Promises may have been broken, but Second Ward will never be broken.”