Did you know Huntersville, North Carolina, was home to northern Mecklenburg County’s first public high school for Black students: Huntersville Colored High School (later Torrence-Lytle High School)? Today, many people interact with Torrence-Lytle through the David B. Waymer Recreation and Senior Center (302 Holbrooks Road, Huntersville, NC), the school’s former gymnasium.

In the early twentieth century, there were no opportunities for high school education for rural Black children in their communities. Black students from Huntersville and the surrounding areas had go to other places for high school education. Families that could afford it sent their children to boarding schools.

Until 1907, high schools only existed in special tax districts; that same year, the North Carolina General Assembly authorized the establishment of rural high schools. The first Compulsory Attendance Act (C.A.C.) was passed in 1913, requiring all children between eight and twelve to attend school for at least four months out of the year.

The early twentieth century was a time in which Black communities experienced extreme levels of segregation and unequal allocation of resources including education. In 1913, the North Carolina Legislature passed legislation that allowed counties to issue bonds to construct high schools for Black children.

There were no options for Black families in Mecklenburg County who wanted their children to have a high school education. There were Rosenwald schools in Mecklenburg County, but they were all elementary schools. The Julius Rosenwald Fund provided architectural plans for schools and the matching funding to build the schools to educate Black students.

Charlotte didn’t open its first school for African American children until Second Ward High School in 1923. Second Ward High School was not a Rosenwald school; its funding came from the City of Charlotte. Some rural Black families sent their children to live in the city with relatives so they could attend Second Ward High School.

By July of 1935, Isaiah Torrence, future namesake of Torrence-Lytle High School, appeared before the Board of County Commissioners (BOCC) seeking funding for a high school for Black students. Mecklenburg County requested $242,000 in funding from the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works Administration to improve and enhance school buildings. Later that year, Torrence appeared before the BOCC again in September asking for funding to build a high school, this time bringing Black residents from Huntersville with him.

In July of 1936, Mecklenburg County approved the construction of four rural high schools for African American children: Pineville Colored High School, Plato Price High School, J.H. Gunn High School, and Huntersville Colored School. The BOCC specifically awarded $35,300 for building a new school in Huntersville. A year later, in 1937, Huntersville Colored High School opened.

The school was in a historically Black section of Huntersville called Pottstown. Pottstown was named for a brick mason, who was a prominent member of the community Ortho Potts. The original Huntersville Colored High School was surrounded by Pott’s farm, a few frame houses, and Huntersville A.M.E. Zion Church.

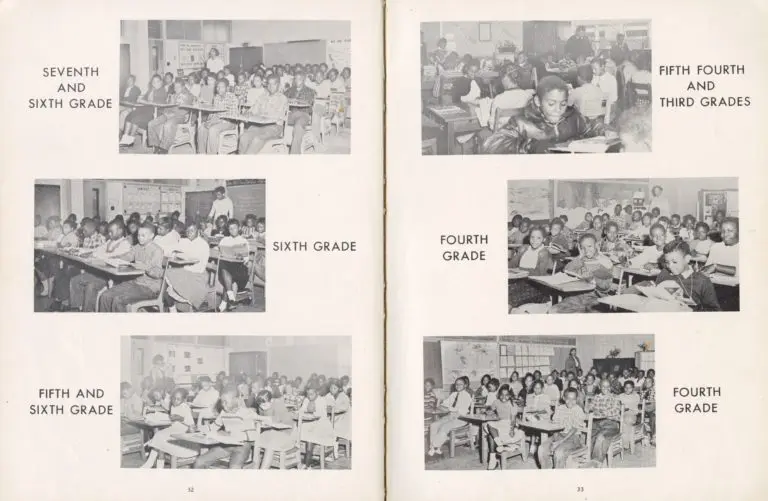

When the school opened in 1937, it was a “union school” that housed grades 1-12. It had seven rooms that housed three elementary school teachers, two high school teachers, principal Isaac T. Graham, and 181 pupils.

By the fall of 1952, the school had to expand its physical space, adding a cafeteria and eight more classrooms to meet the needs of a growing student population. A year later, Huntersville Colored School changed its name to Torrence-Lytle High School to honor Isaiah Dale “Ike” Torrence and Franklin Lytle. Torrence and Lytle were staunch supporters of Black education in northern Mecklenburg County.

Isaiah Torrence worked as a farm agent for part of his life and was believed to be a music teacher and coach, he was a devoted supporter of Black education in northern Mecklenburg County. Franklin Lytle was born enslaved, and little is known of his early life. He became an influential farmer in his community and married Lois Alexander, a schoolteacher. Lytle was an integral part of the establishment of Lytle’s Grove Colored School, a Rosenwald school. He also helped get the land for Torrence-Lytle High School.

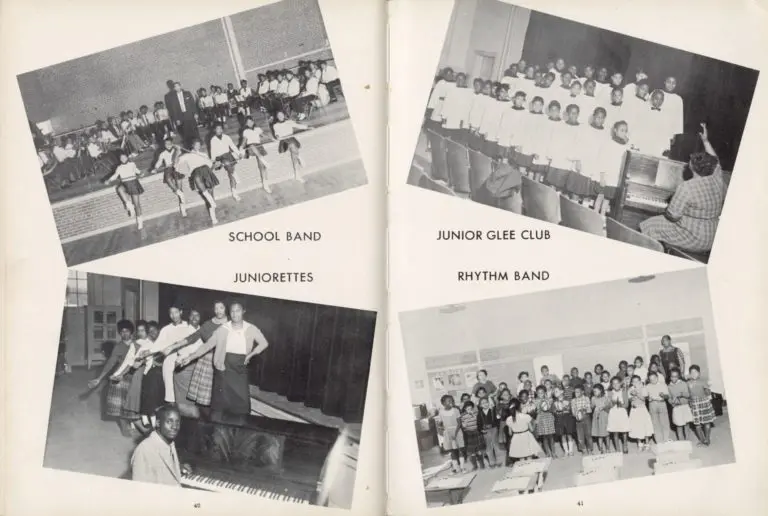

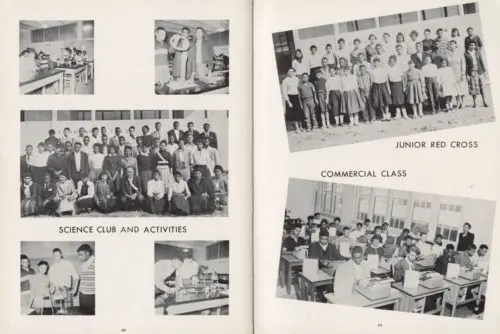

In 1957, the school expanded again, adding 12 classrooms, a home economics department, a gym, an agricultural building, and a science lab. By 1965, some students were beginning to be reassigned to North Mecklenburg High School, and all students were reassigned to racially integrated schools in 1966 resulting in the school closing. After its closing, the campus was used for various purposes, such as an alternative learning center, a recreation center, and storage for Huntersville and Mecklenburg County.

Today, the property has become dilapidated; there have been plans to sell the property and even demolish it. One 1964 graduate of Torrence-Lytle High School, Betty Jane “Bee Jay” Caldwell, has organized alumni and the Pottstown community to protect the school. Caldwell recalled that the school was the “center of the universe” for the Black residents of northern Mecklenburg County.

Caldwell organized protests and ensured that the Charlotte Mecklenburg Land Commission knew of the school’s status as a site for potential demolition. As of 2009, Torrence-Lytle High School is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The school was also designated as a local historic landmark in 2005.

In 2015, the David B. Waymer Center, the school’s gymnasium, was threatened with demolition because county officials believed its old electrical system and possible asbestos contamination made the gym too expensive to repair. The center first opened in 1957. The alumni, most notably Bee Jay Caldwell and residents of the Pottstown neighborhood, opposed the gym’s demolition, starting an anti-demolition campaign. Their campaign did not go unsupported, in 2020 the David B. Waymer Center was restored.

Torrence-Lytle High School is the only remaining Black school in northern Mecklenburg County. It is representative of the struggle African Americans faced in seeking equity and perseverance in their quest for education.